Oki, Nikso’kowaiks.

Greetings to all of my friends and relations.

Art, Culture, and Adventure are the foundation on which I am building my artist’s brand. Whether I am introducing you to an artist or activist who inspired me or exploring the Florida Everglades, I want you all to be able to appreciate the stories behind my paintings. It is one thing to see and another to understand, but it is best if you can experience art.

It is always nice to make a sale, but the real reward comes from making connections. Working alongside people who inspire me, collaborating on things that inspire them, and sharing those experiences with an audience together is my goal for the Marks the Spot project. I want to introduce you to the people and places that inspire me and take you with me when I do the things I am passionate about!

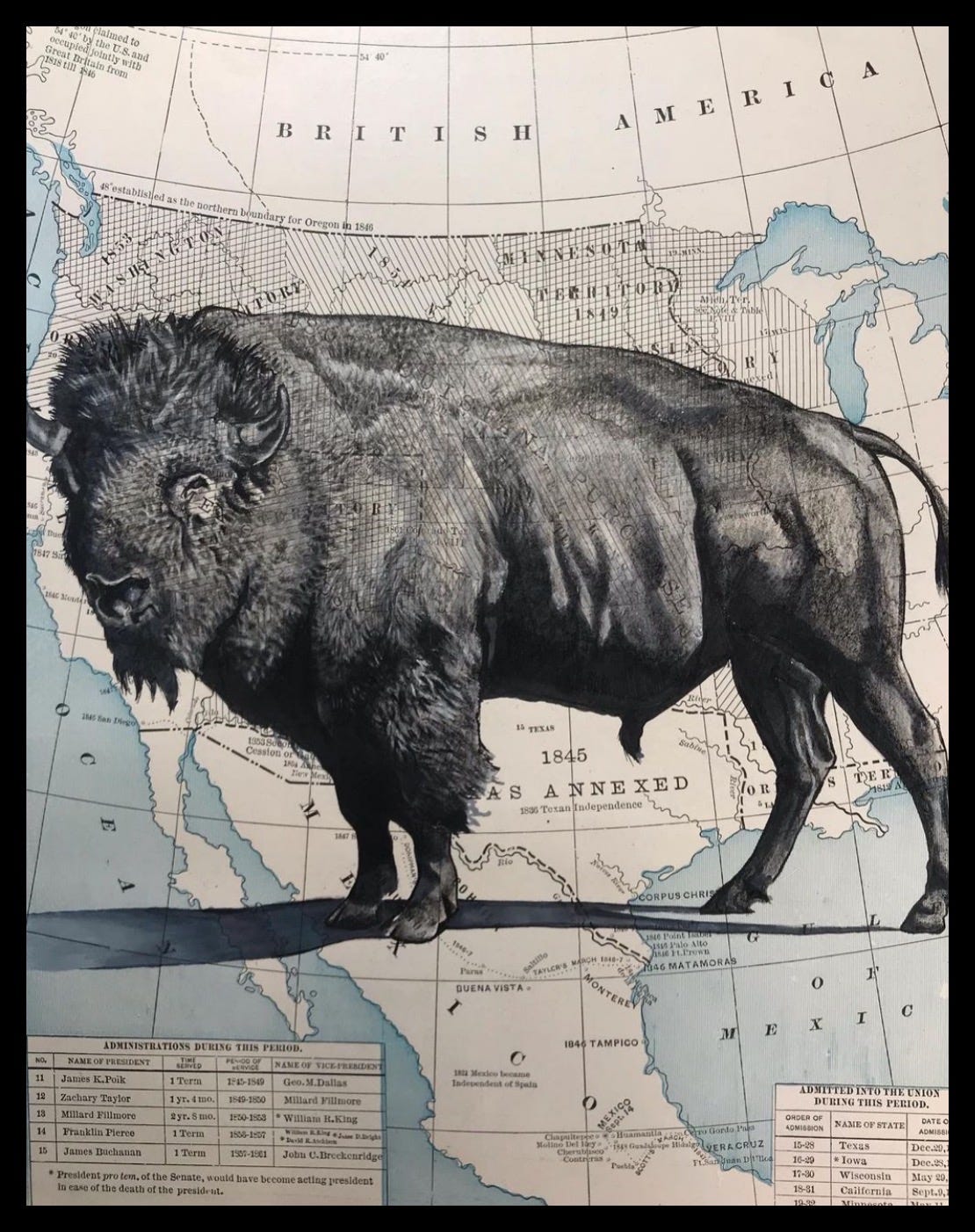

I first gained recognition and gallery representation through my Plains Indian Ledger Art, and it makes sense for me to talk about that here. The practice is all but unheard of east of the Mississippi. I have found that many do not know what Ledger Art is. Over the next four weeks, I will publish this series, The Art of the Ledger, and explain it in the way it was explained to me by Blackfeet artists and elders.

If you have been raised with American history books, this story may not align with your perception of history. Also, Blackfoot ways of knowing and thinking are not the same as nonnative society. There is no written history. Their stories have been passed down from generation to generation through the voices of the elders and storytellers. In their language is a deep connection to the natural world not found in modern English. Throughout this series, there may be questions you have that do not get a satisfactory answer. I have learned to simply accept these answers as true, and that understanding will come in time.

As an outsider, opening the door to the Blackfoot culture was challenging. It remained closed to me because to them I was another náápiikoan —another white man looking to take something. And looking back, I was the epitome of the ignorant white man stereotype. I approached things with a sense of entitlement, and no understanding of protocols or even how to listen. Looking back through “Indian Eyes,” I understand why that door was closed to me. I cringe thinking of things that I said and did.

Through the magic of art (and the marvels of social media), I would eventually connect with three individuals who were well respected by their people that would become my friends. They were patient enough with me to show me the value of closing my mouth and opening my ears. Eventually, I was invited to Indian Country, where I saw the culture for the first time as a living, breathing thing, and not just a scene from a movie. For the first time, I also understood the word “community.”

While I was there, I sat outside the lodge and listened to an elder as he spoke to me while the camp was still sleeping. It was when the sun had risen but had not yet cleared the top of the mountains, and everything was still tinged with grey from the faux dawn. He told me he had never heard the phrase “Turtle Island” until after he had been teaching for a while. He said it was a “young people phrase,” and while he understood the younger generation’s push for unity, he had concerns about the homogenization of Indigenous Culture.

Not all Indians wear buckskins and big flowing eagle feather war bonnets. Not all Natives paddle around in birch bark canoes. Not all erected totem poles. Tragically, not all were as fortunate as the Blackfoot Confederacy, who had not been pushed out of their ancestral lands during the Reservation Era. With almost 575 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone, the diversity of language and culture was incredible.

I began to understand how blessed the Blackfeet are to have had their own unique culture survive, and it is evident in their art. It survived and was passed down from one generation to the next.

What I will tell you here is completely true and accurate from the perspective of someone who grew up far from the reservation and who is only just starting the long journey of reconnecting. It is true and accurate from my experience and my point of view. Wherever possible, I will cite sources and do my absolute best to represent the culture respectfully.

I am imperfect and will make mistakes.

I owe a huge debt to Ledger Art and the Blackfeet who shared it with me. That debt can never be repaid. It filled a void felt since my childhood. It is a sacred practice of creation that breathes life into the inanimate page. This creation brings forth a story—the shared knowledge of who we are and where we come from. This art form has blessed me with friendships, family connections, and a history I had been separated from my entire life.

If I can share that with you, if I can get you to see even a little bit through “Indian eyes,” your appreciation of this art form and the Indigenous artists who practice it can change the very way you see the world.