Oki, Nikso’kowaiks.

This week, I continue my four-part series on the history of Ledger Art. Last week, I told you all why it was important to me personally. In this installment, we will discuss the tradition’s history and origins.

WHAT IS LEDGER ART?

The most concise and easily understandable definition of ledger art I have found was from Sasha Dowdy’s 2023 essay entitled, “The Visual Poetry of Ledger Art: ‘Native American Arts’ Display at the Library of Congress.“ In it, Dowdy wrote, “Male Plains Indian artists began to create representational art on pages of found paper-based products introduced through settler and military colonialism.”

While this art form holds special significance for the Blackfeet, Crow, and Lakota people, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society, the majority of early ledger art came from the “Cheyenne, Arapaho, and the Kiowa of the southern plains, due to the common experience of their incarceration in Florida.”

Florida? How does the Southeasternmost state in the country have any bearing on the American West? Well, the State of Florida has a long, unpleasant history with Indigenous people. It could almost be said that it is ground zero for the assimilation and genocide of the next 195 years. Fort Marion in St. Augustine (now Castillo de San Marcos) saw three separate periods of Indigenous internment.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which required all Indigenous populations east of the Mississippi River to relocate to the West. Each tribe would negotiate its terms for relocation and be granted lands in the new Indian Territory, now the State of Oklahoma. The Treaty of Payne’s Landing was negotiated in 1832 and permitted Miccasukkee leadership to survey the lands assigned to the Seminole before relocation. This process was given a deadline of three years.

1835, the U.S. government sent Major Francis Dade to enforce the treaty. On December 28th, Dade and his detachment set out for Fort King, where they were ambushed by Micanopy and 180 Seminole warriors. Of Dade’s 107 troops, only one survived. Thus began the Second Seminole War, arguably the most violent campaign against Native Americans in history. This conflict would see a number of Seminoles, including Osceola, imprisoned in Fort Marion. While this marked the first time Indigenous people were imprisoned in St. Augustine, it would not be the last.

The “Florida Boys” arrived in 1875 under the charge of Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt. Pratt is known for the development and implementation of “educational” programs that would, as he put it, “Kill the Indian and save the man.” These methods would be at the forefront of the next 120 years of government-sponsored abuse, rape, and murder of thousands of Indigenous children placed in Residential Schools. The effects of Pratt’s policies and the involvement of the Church in an attempt to make Christians of the native people are still felt today. Prisoners of the Indian wars were secured in Ft. Marion. In 1886, train cars delivered men, women, and children—prisoners that included the family of Geronimo, into the custody of the Federal Government. By 1887, more than four hundred captives were held in Fort Marion’s twenty-acre facility.

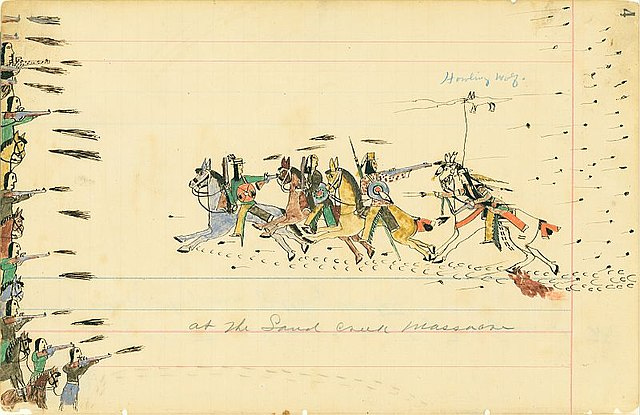

Imprisoned here, far from home and their families, prisoners would draw pictures on the paper provided by their captors. Prisoners would depict battles, including the notorious Sand Creek Massacre, ceremonial life, and their changing world. This caught the attention of their guards, fort officials, and visitors, and for a time, prisoners were even encouraged to sell their drawings. To the white settler, the novelty of owning a “real Indian” drawing was worth the price. But, what they failed to realize was that this early ledger art was preserving the very traditions and history that their captors were trying to erase, and they were doing it right under the very noses—and with the approval of their oppressors.

In this way, Ledger Art can be seen as a form of protest or rebellion. Throughout history, when people are oppressed, they will resist. The resilience of the spirit is one of the things that makes us human. This resilience often manifests itself through art, sending a message of hope and defiance to all who see it. The Art of the Ledger, as we think of it today, came from a dark time when the buffalo had been eradicated, and the traditional ways of many tribes had been lost.

Through this lens, Ledger Art is spitting in the face of oppression, assimilation, and genocide. It is the statement, “We are still here.” Even though the Ledger Art we think of today may have been born in St. Augustine, the tradition of documenting important events in these ways is much older than Ft. Marion.

It is even older than paper…